New outcomes from the primary archaeological fieldwork performed in space present the Worldwide House Station is a wealthy cultural panorama the place crew create their very own “gravity” to exchange Earth’s, and adapt module areas to swimsuit their wants.

Archaeology is often considered the research of the distant previous, nevertheless it’s ideally suited to revealing how folks adapt to long-duration spaceflight.

Within the SQuARE experiment described in our new paper in PLOS ONE, we re-imagined a typical archaeological methodology to be used in space, and received astronauts to hold it out for us.

Archaeology … in … spaaaaace!

The Worldwide House Station is the primary everlasting human settlement in space. Near 280 folks have visited it prior to now 23 years.

Our group has studied shows of photos, religious icons and artworks made by crew members from completely different international locations, observed the cargo that’s returned to Earth, and used NASA’s historic picture archive to look at the relationships between crew members who serve collectively.

We’ve additionally studied the straightforward applied sciences, akin to Velcro and resealable plastic baggage, which astronauts use to recreate the Earthly impact of gravity within the microgravity surroundings – to maintain issues the place you left them, so that they don’t float away.

Most lately, we collected information about how crew used objects contained in the space station by adapting one of the crucial conventional archaeological methods, the “shovel check pit”.

On Earth, after an archaeological web site has been recognized, a grid of one-metre squares is laid out, and a few of these are excavated as “check pits”. These samples give a way of the positioning as an entire.

In January 2022, we requested the space station crew to put out 5 roughly sq. pattern areas. We selected the sq. areas to embody zones of labor, science, train and leisure. The crew additionally chosen a sixth space primarily based on their very own concept of what is perhaps attention-grabbing to look at. Our research was sponsored by the Worldwide House Station Nationwide Laboratory.

Then, for 60 days, the crew photographed every sq. each day to doc the objects inside its boundaries. All the pieces in space tradition has an acronym, so we referred to as this exercise the Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Analysis Experiment, or SQuARE.

The ensuing pictures present the richness of the space station’s cultural panorama, whereas additionally revealing how far life in space is from pictures of sci-fi creativeness.

The space station is cluttered and chaotic, cramped and soiled. There aren’t any boundaries between the place the crew works and the place they relaxation. There may be little to no privateness. There isn’t even a bathe.

What we noticed within the squares

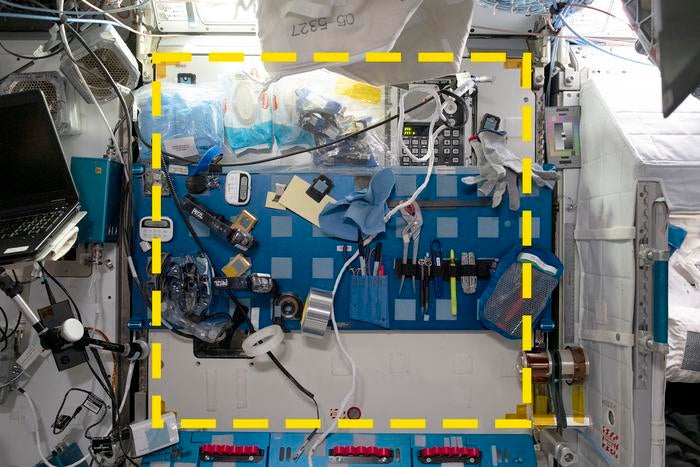

Now we will current outcomes from the evaluation of the primary two squares. One was situated within the US Node 2 module, the place there are 4 crew berths, and connections to the European and Japanese labs. Visiting spacecraft typically dock right here. Our goal was a wall the place the Upkeep Work Space, or MWA, is situated. There’s a blue metallic panel with 40 velcro squares on it, and a desk beneath for fixing gear or doing experiments.

NASA supposed the world for use for upkeep. Nonetheless, we noticed hardly any proof of upkeep there, and solely a handful of science actions. In actual fact, for 50 of the 60 days coated by our survey, the sq. was solely used for storing objects, which can not even have been used there.

The quantity of velcro right here made it an ideal location for advert hoc storage. Near half of all objects recorded (44%) had been associated to holding different objects in place.

The opposite sq. we’ve accomplished was within the US Node 3 module, the place there are train machines and the bathroom. It’s additionally a passageway to the crew’s favorite a part of the space station, the seven-sided cupola window, and to storage modules.

This wall had no designated perform, so it was used for eclectic functions, akin to storing a laptop computer, an antibacterial experiment and resealable baggage. And for 52 days throughout SQuARE, it was additionally the placement the place one crew member stored their toiletry package.

It makes a form of sense to place one’s toiletries close to the bathroom and the train machines that every astronaut makes use of for hours each day. However this can be a extremely public space, the place others are consistently passing by. The location of the toiletry package reveals how insufficient the amenities are for hygiene and privateness.

What does this imply?

Our evaluation of Squares 03 and 05 helped us perceive how restraints akin to velcro create a kind of transient gravity.

Restraints used to carry an object kind a patch of lively gravity, whereas these not in use signify potential gravity. The artefact evaluation reveals us how a lot potential gravity is offered at every location.

The primary focus of the space station is scientific work. To make this occur, astronauts must deploy massive numbers of objects. Sq. 03 reveals how they turned a floor supposed for upkeep right into a midway home for varied objects on their journeys across the station.

Our information means that designers of future space stations, akin to the commercial ones presently deliberate for low Earth orbit, or the Gateway station being constructed for lunar orbit, may have to make storage a better precedence.

Sq. 05 reveals how a public wall space was claimed for private storage by an unknown crew member. We already know there’s less-than-ideal provision for privateness, however the persistence of the toiletry bag at this location reveals how crew adapt areas to make up for this.

What makes our conclusions important is that they’re evidence-based. The evaluation of the primary two squares suggests the information from all six will provide additional insights into humanity’s longest surviving space habitat.

Present plans are to deliver the space station down from orbit in 2031, so this experiment could be the solely likelihood we’ve got to collect archaeological information.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of our collaborators Shawn Graham, Chantal Brousseau, and Salma Abdullah.

Justin St. P. Walsh, Professor of artwork historical past, archaeology, and space research, Chapman University and Alice Gorman, Affiliate Professor in Archaeology and House Research, Flinders University

This text is republished from The Conversation below a Inventive Commons license. Learn the original article.