Earth at perihelion in January

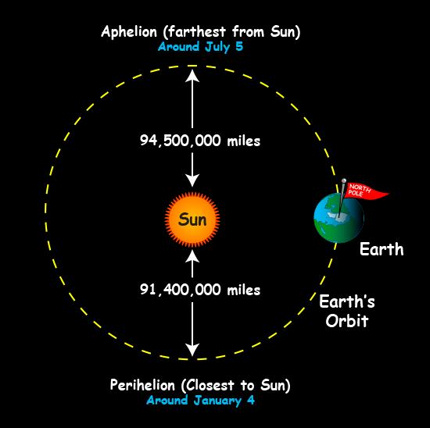

Earth’s orbit across the sun isn’t a circle. As an alternative, it’s an ellipse, like a circle somebody sat down on. So, it is smart that Earth has closest and farthest factors from the sun annually. For 2023, our closest level comes at 16 UTC (10 a.m. CST) on January 4 … That is the morning in North America. This closest Earth-sun distance is known as perihelion, from the Greek roots peri which means close to and helios which means sun. In early January, we’re about 3% nearer to the sun – roughly 3 million miles (5 million km) – than we’re throughout Earth’s aphelion (farthest level) in early July. That’s in distinction to our common distance of about 93 million miles (150 million km).

NASA Earth Fact Sheet with precise perihelion and aphelion distances.

So, Earth is closest to the sun yearly in early January, when it’s winter for the Northern Hemisphere.

And we’re farthest away from the sun in early July, throughout our Northern Hemisphere summer time.

Clearly, Earth’s distance from the sun isn’t the reason for the seasons.

Earth’s orbit doesn’t trigger seasons

So, Earth’s orbit isn’t a circle. However it’s practically round. And it’s not our distance from the sun that creates winter and summer time on Earth. As an alternative, the lean of our world’s axis with respect to our orbit causes seasons.

In winter, your a part of Earth is tilted away from the sun. In summer time, your a part of Earth is tilted towards the sun. The day of most tilt towards or away from the sun is the December or June solstice.

The lean adjustments the angle of daylight falling in your a part of Earth. Extra direct daylight = summer time. Much less direct daylight = winter.

Earth’s orbit impacts size of the seasons

Although not chargeable for the seasons, Earth’s closest and farthest factors to the sun do have an effect on seasonal lengths. When the Earth comes closest to the sun for the 12 months, as we do yearly in early January, our world is shifting quickest in orbit. Earth is dashing alongside now at nearly 19 miles per second (30.3 km/sec), shifting about 0.6 miles per second (one km/sec) quicker than when Earth is farthest from the sun in early July. So the Northern Hemisphere winter and – concurrently – the Southern Hemisphere summer time are the shortest seasons, as Earth rushes from the solstice in December to the equinox in March.

Within the Northern Hemisphere, the summer time season (June solstice to September equinox) lasts practically 5 days longer than our winter season. And this holds true for the corresponding seasons within the Southern Hemisphere, as effectively. Southern Hemisphere winter is almost 5 days longer than Southern Hemisphere summer time.

The 30-second YouTube video beneath illustrates how a planetary physique hastens round perihelion and slows down at aphelion. It’s resulting from Kepler’s second law of planetary movement: a line connecting the sun and a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal instances.

Backside line: In 2023, Earth’s perihelion, its closest level to the sun, is on January 4 at 16 UTC.